Speedrunning with OpenMP

I am going to try and see if I can make it through the Hands-on Introduction to OpenMP in one day. The goal is to learn openMP, with no obsession about being a purist. Googling for help, asking ChatGPT is all allowed as long as I document where I needed help and what exactly it contributed.

Disclaimer, I was introduced to what OpenMP was back in undergrad during our parallel programming class. Unfortunately, it was during COVID which made concentrating on the material very difficult. Anyways, I am not really starting from 0-experience with openMP because I have been exposed to many of the concepts and also am familiar with how operating systems work.

Exercise 1: Hello world

Before we start learning openMP, we first need to get it working on this laptop. First, install with

brew install libomp

Part A is trivially easy, literally hello world with no tricks. We are only discussing part B.

The exercise is to print a multithreaded program where each thread prints hello world. The way we do this is wrapping the parallel portion of the code in a #pragma omp parallel brackets.

My first iteration starts with the following in main.cpp.

#include <iostream>

#include <omp.h>

int main() {

#pragma omp parallel

{

int thread_id = omp_get_thread_num();

std::cout << "Hello World! from thread " << thread_id << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}

However, I am only able to get one thread. I’m not sure I’m correctly calling the openMP library right now. I am very confident that my code is correct because I ran it on my Linux workstation 1 hour ago.

After nearly another hour, I realized that the CMake isn’t good at finding openMP with the find_package function. I had much more luck with a makefile. So change your makefile to this

all:

clang -Xclang -fopenmp -L/opt/homebrew/opt/libomp/lib\

-I/opt/homebrew/opt/libomp/include -lomp -lstdc++ main.cpp -o build/main

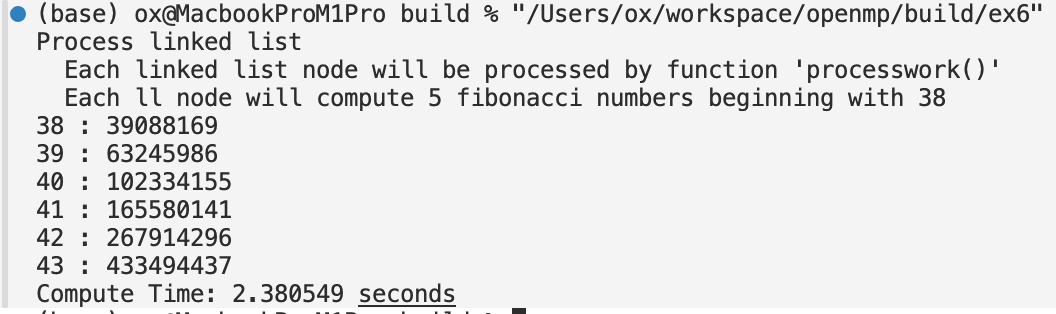

And when you compile, you should get

FYI, this exercise took me about an hour because the Apple M1 Pro CMake does not automatically detect the openMP version so I had to go on stack overflow.

Exercise 2: Numerical Integration

We need to do a heavy numerical integration problem to confirm that running the program in multiple threads is indeed faster than just one thread. Basically, we approximate $\pi$ with

\[\sum^{N}_{i=0} F(x_i)\Delta x\]The serial version of this program is quite easy.

#include <iostream>

#include <omp.h>

static long num_steps = 1000000000;

double step;

int main() {

std::cout << "Serial Mode" << std::endl;

double pi = 0.0;

double sum = 0.0;

double x = 0.0;

int i = 0;

step = 1.0/(double) num_steps;

double start = omp_get_wtime();

for(i = 0; i < num_steps; i++){

x = (i + 0.5)*step;

sum = sum + 4.0/(1.0 + x*x);

}

pi = step * sum;

double end = omp_get_wtime();

std::cout << "Time Taken: " << end - start << " Value: " << pi << std::endl;

return 0;

}

The exercise is to create a parallel version of the program using a parallel construct. The hard part is that we can’t just update sum because the update is not atomic and we will get corrupt the value of sum in the middle of the operation. The idea is to store an array of num_threads in the middle.

int n_threads = omp_get_num_threads();

std::vector<double> partial_sum(n_threads,0);

for(i = 0; i < num_steps; i+= n_threads){

#pragma omp parallel

{

int ID = omp_get_thread_num();

x = (i + ID + 0.5)*step;

partial_sum[ID % n_threads] += 4.0 / (1.0 + x*x);

}

}

sum = 0;

for(i = 0; i < n_threads; i++){

sum += partial_sum[i];

}

pi = step * sum;

end = omp_get_wtime();

std::cout << "Time Taken: " << end - start << " Value: " << pi << std::endl;

This is the code I have that gives me an incorrect answer. Using an LLM, I realized that the ID variable should be outside the for loop. I didn’t think of that.

After about 2 hours of struggling, and taking breaks, and minimal googling. I finally got to this point.

sum = 0;

pi = 0;

x = 0.0;

i = 0;

std::vector<double> arr(NUM_THREADS,0);

#pragma omp parallel

{

int ID = omp_get_thread_num();

if(ID == 0) {

std::cout << "number of threads " << NUM_THREADS << std::endl;

}

for(int i = ID; i < num_steps;i+=NUM_THREADS){

x = (i + 0.5)*step;

arr[ID] += 4.0/(1.0 + x*x);

}

}

for(int it = 0; it < NUM_THREADS;it++){

sum += arr[it];

}

pi = sum * step;

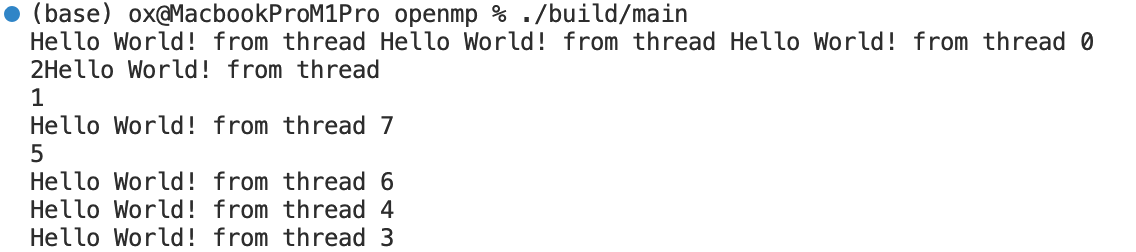

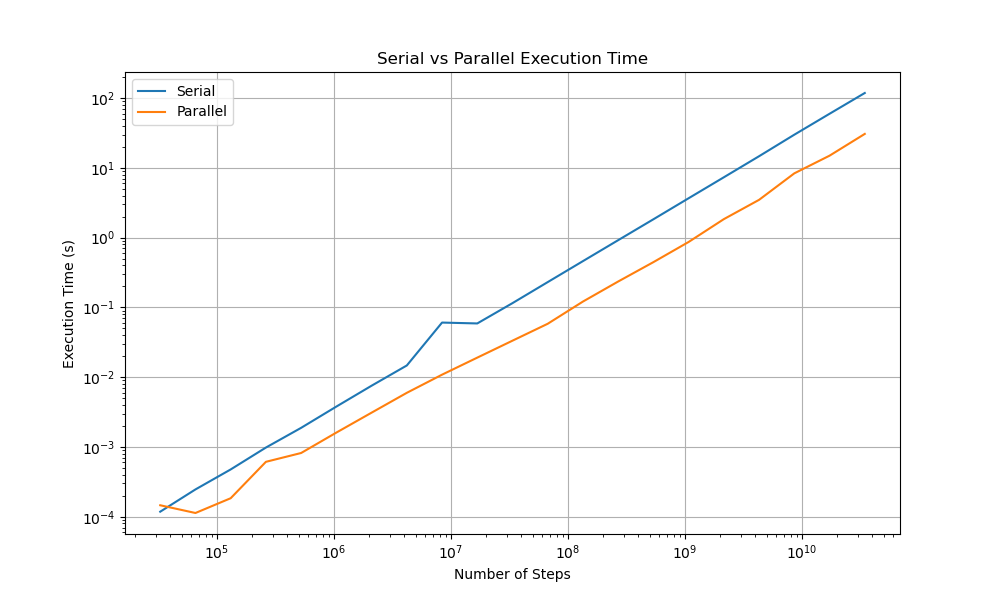

The results are about what you would expect. The parallel version beats the serial version by about 1/2, which is suboptimal because 8 threads are being used. As you can see

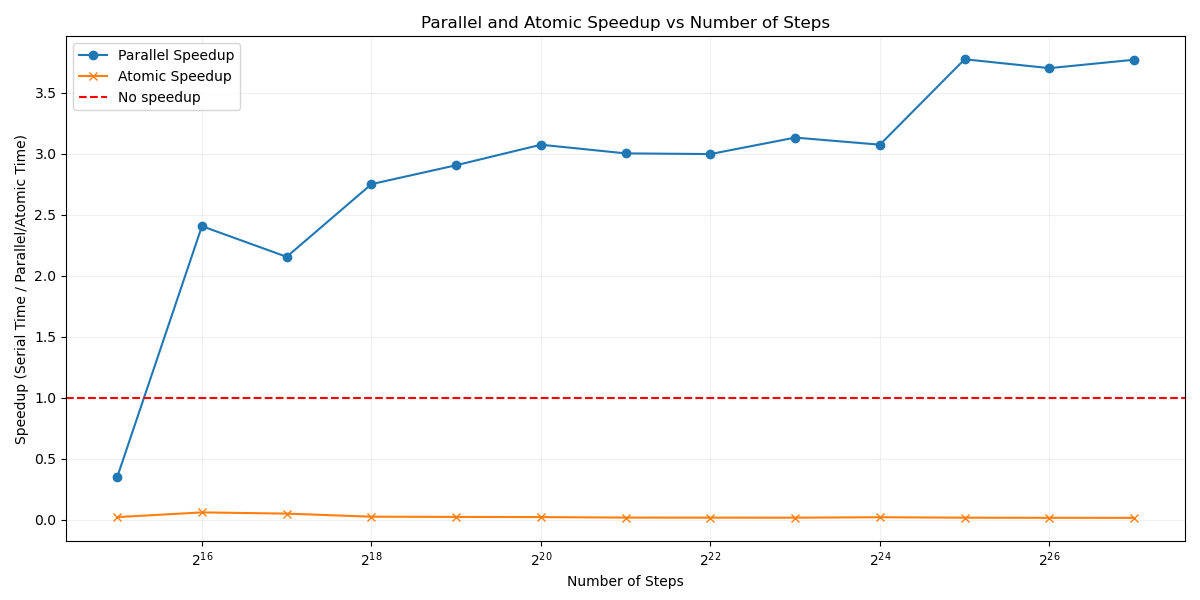

In order to find the exactly how much more efficient parallel processing is, compare the speedup between the serial and parallel execution time. See that  .

.

As you get to the largest number steps (which contains the least amount of noise), the parallel code takes a large 41% percent of the time considering that it was given 8x the computational resources as the serial threading. The theoretically perfect performance is if the parallel version took 12.5% of the time compared to the serial version.

Exercise 3: Fix false sharing

In the previous exercise, we used an array and the ID to store each partial sum to a unique index. However, this is not a good idea in terms of cache performance because each threads independent variables can invalidate and remove the array off of the cache.

Using the #pragma omp atomic, we are able to directly control which variables need to be adjusted carefuly. We create a new fn in ex2.cpp to account for this.

long double calculate_pi_atomic(long num_steps) {

long double step = 1.0L / static_cast<long double>(num_steps);

long double sum = 0.0L;

#pragma omp parallel

{

int ID = omp_get_thread_num();

for (long i = ID; i < num_steps; i += NUM_THREADS) {

long double x = (static_cast<long double>(i) + 0.5L) * step;

#pragma omp atomic

sum += 4.0L / (1.0L + x * x);

}

}

return step * sum;

}

Unfortunately, it looks like this made our code worse because the operations inside the for loop aren’t labor intensive enough, causing the biggest fight to be for the variable to update. I had to stop this iteration short because it would take way too long to finish because most of the time is spend for the threads fighting for permission to update sum.

Comparing the efficiency metric similar to the previous exercise, the efficiency with the atomic instruction is horrible.

Parallel is 4x faster, atomic is 50x slower. It’s not the perfect comparison because atomic instructions are good when the computation being done is far heavier than this case. The atomic case will not be included for the rest of the exercises due to the results ruining the scale for the other benchmarks.

Exercise 4: Parallel loop reduction

OpenMP has the ability to work with the compiler to optimize the way for loops are dealt with. You can use it like this

long double calculate_pi_for_reduce(long num_steps) {

long double step = 1.0L / static_cast<long double>(num_steps);

long double sum = 0.0L;

#pragma omp parallel for reduction(+:sum)

{

for (long i = 0; i < num_steps; i++) {

long double x = (static_cast<long double>(i) + 0.5L) * step;

sum += 4.0L / (1.0L + x * x);

}

}

return step * sum;

}

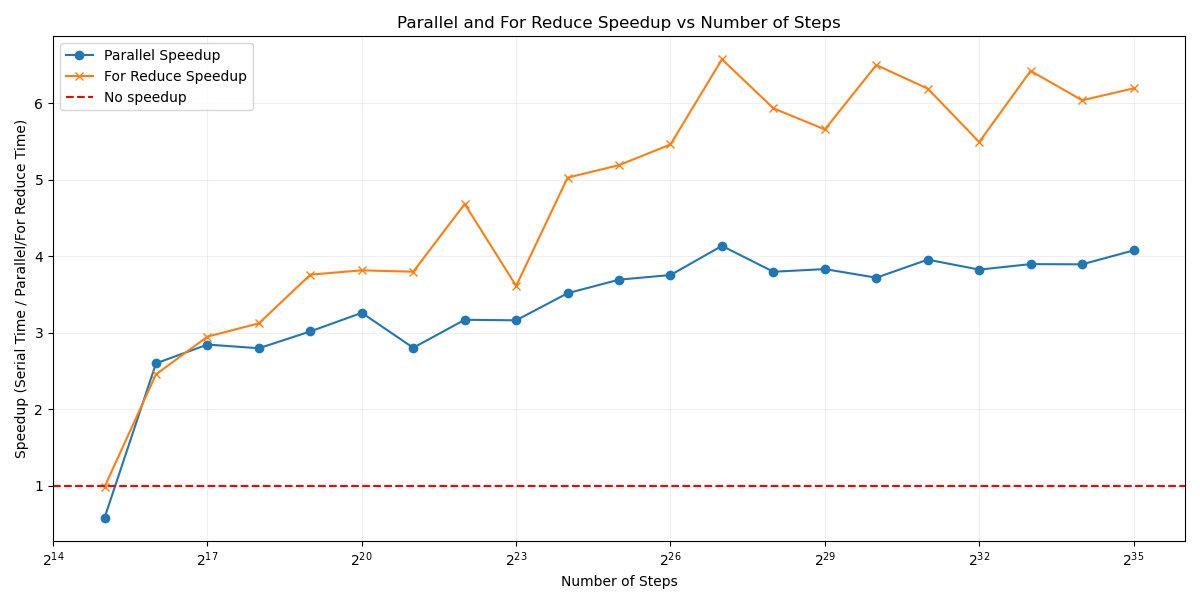

If there is an accumulated value inside a for loop (a reduction), then use the for reduction. The compiler finds better instructions containing the op, and uses those in each thread. This is much faster than the previous optimizations, and the results reflect that

The Parallel For Reduce reached an efficiency of 59%, I thought I would be able to get to at least 75% efficiency. 60% efficiency seems rather low for me.

In other words, the speedup for parallel, is approximately 4.14 and the speedup for for-reduce is 6.58.

Further Work

- Compare the distribution of the actual cpu instructions used in the executable for the different functions.

- Figure out if the 60% efficiency is due to clang’s compiler being bad.

Synchronization: Barrier

A barrier forces each thread to wait untill all threads arrive. By default, after every for loop there is an implicit barrier, that you can bypass with pragma omp for nowait.

Master construct

Using pragma omp master, designate only the master thread to do the work. The master thread initiates and terminates parallel regions.

Single Construct

pragma omp single can be used when one thread, not necessarily master, needs to do work

Exercise 5: Monte Carlo Calculations

First I am going to talk about a few extra commands that may end up useful later. Here is the starter code that you will need

pi_mc.c

/*

NAME:

Pi_mc: PI Monte Carlo

Purpose:

This program uses a Monte Carlo algorithm to compute PI as an

example of how random number generators are used to solve problems.

Note that if your goal is to find digits of pi, there are much

better algorithms you could use.

Usage:

To keep the program as simple as possible, you must edit the file

and change the value of num_trials to change the number of samples

used. Then compile and run the program.

Algorithm:

The basic idea behind the algorithm is easy to visualize. Draw a

square on a wall. Inside the square, draw a circle. Now randomly throw

darts at the wall. some darts will land inside the square. Of those,

some will fall inside the circle. The probability of landing inside

the circle or the square is proportional to their areas.

We can use a random number generator to "throw the darts" and count

how many "darts" fall inside the square and how many inside the

cicle. Dividing these two numbers gives us the ratio of their areas

and from that we can compute pi.

Algorithm details:

To turn this into code, I need a bit more detail. Assume the circle

is centered inside the square. the circle will have a radius of r and

each side of the square will be of area 2*r (i.e. the diameter of the

circle).

A(circle) = pi * r^2

A(square) = (2*r)*(2*r) = 4*r^2

ratio = A(circle)/A(square) = pi/4

Since the probability (P) of a dart falling inside a figure (i.e. the square

or the circle) is proportional to the area, we have

ratio = P(circle)/P(square) = pi/4

If I throw N darts as computed by random numbers evenly distributed

over the area of the square

P(sqaure) = N/N .... i.e. every dart lands in the square

P(circle) = N(circle)/N

ratio = (N(circle)/N)/(N/N) = N(circle)/N

Hence, to find the area, I compute N random "darts" and count how many fall

inside the circle. The equation for a circle is

x^2 + y^2 = r^2

So I randomly compute "x" and "y" evenly distributed from -r to r and

count the "dart" as falling inside the cicle if

x^2 + y^2 < or = r

Results:

Remember, our goal is to demonstrate a simple monte carlo algorithm,

not compute pi. But just for the record, here are some results (Intel compiler

version 10.0, Windows XP, core duo laptop)

100 3.160000

1000 3.148000

10000 3.154000

100000 3.139920

1000000 3.141456

10000000 3.141590

100000000 3.141581

As a point of reference, the first 7 digits of the true value of pi

is 3.141592

History:

Written by Tim Mattson, 9/2007.

*/

#include <stdio.h>

#include <omp.h>

#include "random.h"

//

// The monte carlo pi program

//

static long num_trials = 10000;

int main ()

{

long i; long Ncirc = 0;

double pi, x, y, test;

double r = 1.0; // radius of circle. Side of squrare is 2*r

seed(-r, r); // The circle and square are centered at the origin

for(i=0;i<num_trials; i++)

{

x = drandom();

y = drandom();

test = x*x + y*y;

if (test <= r*r) Ncirc++;

}

pi = 4.0 * ((double)Ncirc/(double)num_trials);

printf("\n %ld trials, pi is %lf \n",num_trials, pi);

return 0;

}

random.c

//**********************************************************

// Pseudo random number generator:

// double random

// void seed (lower_limit, higher_limit)

//**********************************************************

//

// A simple linear congruential random number generator

// (Numerical Recipies chapter 7, 1st ed.) with parameters

// from the table on page 198j.

//

// Uses a linear congruential generator to return a value between

// 0 and 1, then scales and shifts it to fill the desired range. This

// range is set when the random number generator seed is called.

//

// USAGE:

//

// pseudo random sequence is seeded with a range

//

// void seed(lower_limit, higher_limit)

//

// and then subsequent calls to the random number generator generates values

// in the sequence:

//

// double drandom()

//

// History:

// Written by Tim Mattson, 9/2007.

// changed to drandom() to avoid collision with standard libraries, 11/2011

static long MULTIPLIER = 1366;

static long ADDEND = 150889;

static long PMOD = 714025;

long random_last = 0;

double random_low, random_hi;

double drandom()

{

long random_next;

double ret_val;

//

// compute an integer random number from zero to mod

//

random_next = (MULTIPLIER * random_last + ADDEND)% PMOD;

random_last = random_next;

//

// shift into preset range

//

ret_val = ((double)random_next/(double)PMOD)*(random_hi-random_low)+random_low;

return ret_val;

}

//

// set the seed and the range

//

void seed(double low_in, double hi_in)

{

if(low_in < hi_in)

{

random_low = low_in;

random_hi = hi_in;

}

else

{

random_low = hi_in;

random_hi = low_in;

}

random_last = PMOD/ADDEND; // just pick something

}

//**********************************************************

// end of pseudo random generator code.

//**********************************************************

random.h

double drandom();

void seed(double low_in, double hi_in);

I actually accidentally saw the answer, but I’m not good enough at openMP that 2 seconds of looking at the answer compresses the information enough for it to be useful to me. What I did see was one #pragma omp XXX private XXX reductionXX. So now I just have to fill in the blanks.

So I am abandoning this exercise because I am seeing not speedup even after looking at the “solution”. In fact the solution isn’t numerically stable and around 30% slower. I don’t know what happened. On my Mac M1 Pro, Single-Threaded takes ~2.1 seconds and Parallel takes ~2.6 seconds.

Exercise 6: hard, linked lists without tasks

I didn’t include the link for the exercises previously because exercise 5 included the answer by accident. However, this one does not and the starter code is in this repository. I will also copy the starter code down below so that you don’t need to go hunting for it on that site.

linked.c

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <omp.h>

#ifndef N

#define N 5

#endif

#ifndef FS

#define FS 38

#endif

struct node {

int data;

int fibdata;

struct node* next;

};

int fib(int n) {

int x, y;

if (n < 2) {

return (n);

} else {

x = fib(n - 1);

y = fib(n - 2);

return (x + y);

}

}

void processwork(struct node* p)

{

int n;

n = p->data;

p->fibdata = fib(n);

}

struct node* init_list(struct node* p) {

int i;

struct node* head = NULL;

struct node* temp = NULL;

head = (struct node*)malloc(sizeof(struct node));

p = head;

p->data = FS;

p->fibdata = 0;

for (i=0; i< N; i++) {

temp = (struct node*)malloc(sizeof(struct node));

p->next = temp;

p = temp;

p->data = FS + i + 1;

p->fibdata = i+1;

}

p->next = NULL;

return head;

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

double start, end;

struct node *p=NULL;

struct node *temp=NULL;

struct node *head=NULL;

printf("Process linked list\n");

printf(" Each linked list node will be processed by function 'processwork()'\n");

printf(" Each ll node will compute %d fibonacci numbers beginning with %d\n",N,FS);

p = init_list(p);

head = p;

start = omp_get_wtime();

{

while (p != NULL) {

processwork(p);

p = p->next;

}

}

end = omp_get_wtime();

p = head;

while (p != NULL) {

printf("%d : %d\n",p->data, p->fibdata);

temp = p->next;

free (p);

p = temp;

}

free (p);

fffƒƒƒ

printf("Compute Time: %f seconds\n", end - start);

return 0;

}

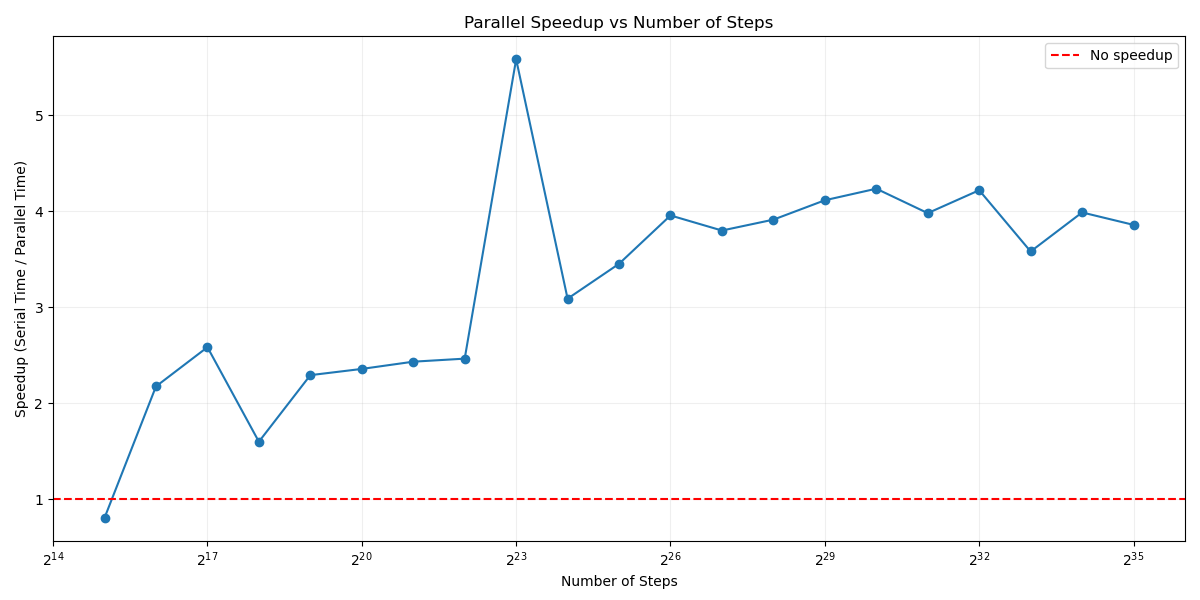

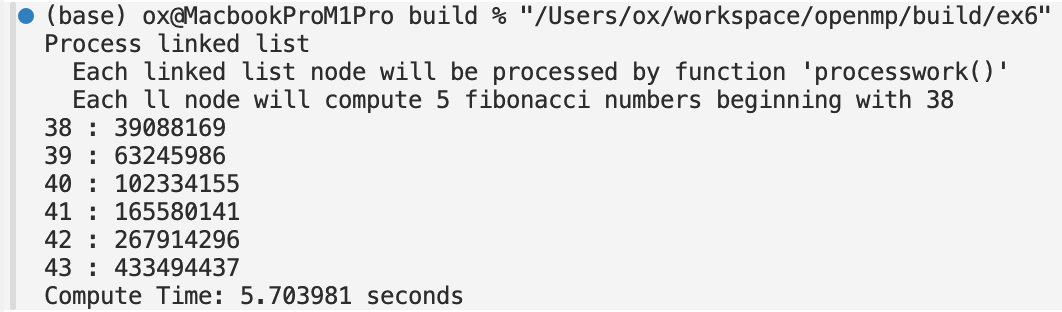

Running the list synchronously, I get approximately 6 seconds runtime.

It wasn’t immediately obvious to me how to parallelize a linked list. My idea was to multiple threads at the beginning of the linked list, each with thread_id offset. Then when a thread is finished processing, call $p=p.next$ thread_num times. However, there was only 5 nodes, so convert the linked list into an array, then use a parallel for loop to process the array. FYI, I did use chatGPT to implement this. I didn’t want to be stuck getting trivial, obscure pointer code working.